HI RES / MID RES

HI RES / MID RES

HI RES / MID RES

HI RES / MID RES

HI RES / MID RES

HI RES / MID RES

HI RES / MID RES

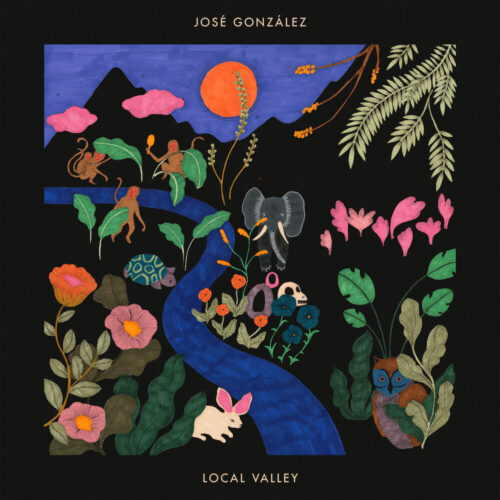

Artwork by Hannele Fernström

HI RES / MID RES

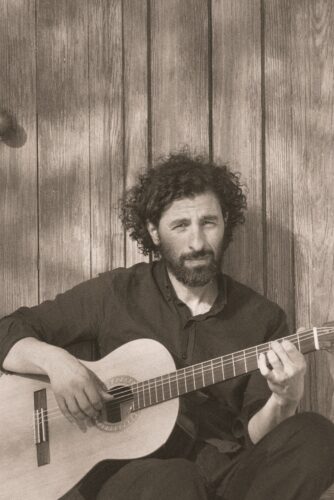

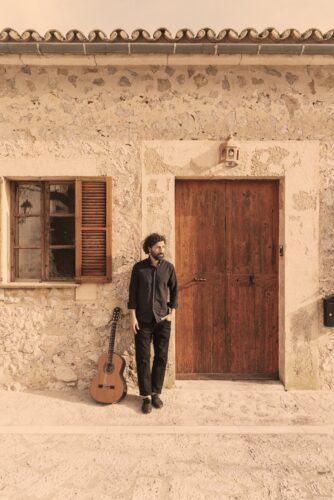

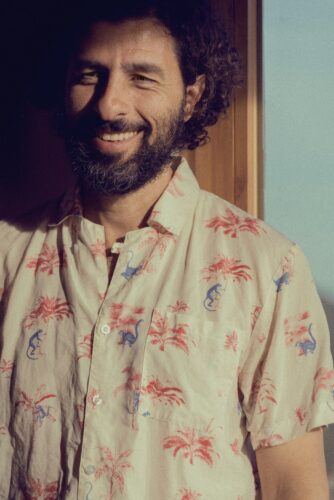

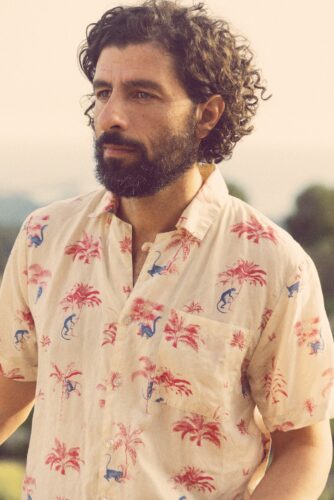

José González: Local Valley

It’s easy to overlook the fact that, despite only three solo albums in 18 years, José González has packed out distinguished venues from Sydney to Tallinn – via Berlin, Barcelona and Rio De Janeiro – and even sold out London’s prestigious, 4000+ capacity Royal Albert Hall a full three years after his last acclaimed collection, 2015’s Vestiges & Claws. He’s earned platinum records in the UK and his Swedish homeland as well gold in Australia and New Zealand. He’s also got some billion streams under his belt, and recent bewildering events have only endeared him further to the public, with his songs providing a consistent source of comfort over the last 18 months, something reflected by a significant rise in those streaming figures. Of course, such matters aren’t things of which José himself will remind you: since he first arrived with debut single ‘Crosses’ back in 2003, both he and his music have remained dependably quiet and unassuming. To underestimate him on account of his modest nature, however, would certainly be regrettable.

José’s long-awaited fourth album, Local Valley, provides a welcome reminder of his understated appeal and his singular ability to communicate discreetly, a quality illustrated by the uncommonly effective use of his music during The Last Dance, Netflix’s recent documentary about Michael Jordan. Local Valley also for the first time utilises all three languages José speaks, allowing for greater depth and connection to his lineage. Beginning with the sun-dappled ‘El Invento’, the first song he’s recorded in Spanish (the native tongue of his Argentinian heritage), and ending with the intimate yet rhapsodic ‘Honey Honey’, it engages in his signature melodic and metrical hypnotism on ‘Head On’ and ‘Tjomme’ and showcases his impressive fingerpicking skills on ‘Valle Local’, while there’s evidence of his love for music from around the world in ‘Swing’, among other tracks.

It’s also full of his trademark, bittersweet pastoralism, including ‘Visions’ and ‘Horizons – which, alongside ‘El Invento’, José considers “my most accomplished songs to date” – not to mention ‘The Void’, ‘Lasso In’, and of course ‘Line Of Fire’, which continues his tradition of reinterpreting songs, though on this occasion he picks one written for Junip, the band he formed with friends in 1998, which, after two albums, he continues to maintain with co-founder Tobias Winterkorn. That the original version has now been streamed some 60 million times suggests it, like other songs he’s covered, is now part of the songwriting canon.

Local Valley, José cheerfully acknowledges, “is similar to my other solo albums in sound and spirit, a natural continuation of the styles I’ve been adding through the years both solo and with Junip. I set out to write songs in the same vein as my old ones: short, melodic and rhythmical, a mixture of classic folk singer songwriting and songs with influences from Latin America and Africa. It’s more outward looking than my earlier works, but no less personal. On the contrary, I feel more comfortable than ever saying that this album reflects me and my thoughts right now.”

Certainly, these thirteen meticulously crafted songs sound as confident as anything he’s recorded, and they’re also characteristically rich in compelling detail. This is mirrored in Local Valley’s cover, drawn by his partner, illustrator and designer Hannele Fernström, who also adds her voice to ‘Swing’, and for whom ‘Honey Honey’ was written. While the image appears to depict a sunlit valley filled with animals and plants, there’s typically more to it than meets the eye. The elephant and blackbird at its centre are, José reveals, “a nod to ‘The Rider & The Elephant’, a behavioural psychology model by (NYU psychologist) Jonathan Haidt,” and the textiles of Josef Frank – the founder of the Vienna School of Architecture who spent later life exiled in Sweden – provided its stylistic inspiration. The results, meanwhile, are intended to reflect the album’s title, “a metaphor for both humanity stuck here on earth – our local green valley in a vast, inhospitable universe – and also for two dogmatic tribes stuck in a state where they’re unable to see things from the others’ perspective, preventing them from establishing a more harmonic state.”

Given the intricate, conceptual approach to this artwork, it’s unsurprising to discover that José goal was not only simply to create “good music, beautiful and at times groovy,” but also to be, “at closer glance, intriguing and at times provocative, depending on your worldview.” He’s well placed to delve into complex themes: when not making music or taking care of his daughter, he’s busy investigating topics like effective altruism, secular humanism and ecomodernism, upon which he can sometimes be found expounding amid a likeminded community on Twitter. In fact, he’s often been ahead of the game, musically and sociologically: he studied viruses at Gothenburg University, and his lyrics have frequently addressed previously marginalised themes like the struggle between ‘fake news’ and science, secularism and the environment. He’s also immersed himself in a dizzying range of books published over the last decades by some of the world’s most eminent thinkers: David Christian’s Origin Story: A Big History Of Everything; Alain de Botton’s Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer’s Guide To The Uses Of Religion, Antonio Damasio’s The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures, Daniel Dennett’s From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds, and even Åsa Wikforss’ Alternative Facts: On Knowledge and Its Enemies, so fundamental a text in the 42-year-old’s homeland that it’s available for free to all of Sweden’s third-year high school students.

Spurred on by such research, Local Valley’s lyrics explore associated subjects. “Many songs have a crystal-clear, secular humanist agenda: anti-dogma, pro-reason,” José elaborates. “There’s no political agenda, though, at least not in a classical left-right spectrum. Maybe in a globalist-secular vs theocratic-nationalist way: the focus is on underlying worldviews, and on our existential questions as smart apes on a quest to understand ourselves and our place in the cosmos.” The album, however, is neither intimidatingly impenetrable nor prosaic: like physicist Brian Cox, whose Human Universe afforded another source of insight, José addresses substantial affairs in an accessible manner suited to his music’s apparently ingenuous nature.

As it happens, this is something he’s always done, even if it’s rarely been identified, and that it’s so inconspicuous speaks volumes of José’s ear for nuance. In case there were any doubts about his philosophical intent, however, opener ‘El Invento’ examines questions like ‘Where do we come from?’ then queries the routine answer: God. Forewarned is, therefore, forearmed: take a closer look at ‘Visions’, which picks up where Vestiges & Claws’ ’Every Age’ left off, advocating unity in our search for meaning, or at ‘Valle Local’, which returns to territory from the same album’s ‘Stories We Build, Stories We Tell’. As for ‘Tjomme’ – which bluntly asks “What the fuck are you doing now? / Are you completely deranged?”– it faces up to struggles between progress and tradition first confronted on In Our Nature’s ‘Abram’.

‘Swing’, too, revisits matters first tackled on Vestige & Claws’ ‘Let It Carry You’, pondering “how silly regressive, illiberal theocracies are, with Iran a recent example, where people made their own dance videos to Pharrell Williams’ ‘Happy’ even though it was, and still is, forbidden”. Then there’s ‘The Void’, which, like Junip’s ‘Beginnings’, reviews ideas of cognitive dissonance, and ‘Lasso In’, which – like another Junip song, this time ‘Loops’ – extols the benefits of meditation. “Since my second album,” José confesses, “I’ve usually gone to my own songs for reference, similar to how I sense Beastie Boys did on Check Your Head and their follow up, Ill Communication.” There’s certainly a lot upon which to reflect.

Recorded at Studio Koltrast Hakefjorden, which he set up in his family’s summer house north of Gothenburg – if you listen closely, his ancient laptop’s fan can be heard whirring within wood-panelled walls – Local Valley again finds José alone with just a handful of nylon-stringed Spanish guitars, chosen for their resonances and characters. This time, however – on ‘Lasso In’, ‘Lilla G’, ‘Swing’, and ‘Tjomme’ – he employs an iPad’s DM1 drum machine app, replacing the congas and bongos of 2003’s Veneer and 2007’s In Our Nature and his percussive use of the guitar itself on Vestiges & Claws. “I also allowed myself to loop guitars as I aim to do live with pedals,” he adds, “and in my head I was hearing how each track would fit with an orchestra (The String Theory) or my five-piece band (The Brite Lites), with whom I’ve been touring on and off the last decade.”

There are, however, collaborations – of a sort – on Local Valley that took place outside of José’s head. ‘En Stund På Jorden’ is a cover of a song by Iranian-Swedish artist Laleh – a former refugee who’s topped Swedish charts multiple times after growing up in the same multicultural Gothenburg neighbourhood as he did – while on ‘Honey Honey’ he looks back to ‘Music On My Teeth’, a song from DJ Koze’s 2018 album, Knock Knock, upon which he guested. “Can I also mention,” he adds, “that I had a jam session with Bombino, the artist from Niger, back in 2016 when he hung out in Gothenburg? That, together with his performance on his own with a guitar, was very inspiring while writing ‘Valle Local’ and ‘Head On’.”

‘Lilla G’, meanwhile, was written for his daughter, for whom – and most likely with whom – he’s sung it most of her young life. Given such unabashed intimacy, combined with his eagerness to address grand themes, it seems only appropriate that José first unveiled ‘El Invento’ as part of the 2020 Nobel Prize Award Ceremonies. Four albums in, Local Valley finds him – in the words of ‘Visions’ – “Imagining the worlds that could be / Shaping a mosaic of fates / For all sentient beings.” Few people would – or could – slip such a bold claim into a song so soberly and nimbly, but then again, few people have managed to become quite so celebrated worldwide quite as quietly as José has. What a relief it is to be reminded that you don’t have to be loud to be heard.